the chicken, the pickle, the squid and the whale

So we liked the recent film The Squid and the Whale, directed by Noah Baumbach (much mentioned here, as Ben harbors a romantic attachment based upon Baumbach's nonsensical New Yorker contributions) and produced by Wes Anderson. Bear in mind, we didn't like the Royal Tennenbaums because it was just too precious and aren't-we-special-and-clever. My dad thought that one of the track suit twins in that movie should have been a girl.

Actually, we were walking very briskly to the theater to see Good Night and Good Luck because I love fictional-historical bio-pics (though not documentaries, as you may know) but we were late and we knew it and when we got there we found that The Squid and The Whale was just starting. I think my partner in crime may have manipulated this whole thing.

And then together, on the way home, he drew me into an analysis of why it was a very good film.

To begin, we didn't find the dad as unsympathetic as some reviewers - a long sort of biographical thing on Baumbach Jr. and Baumbach Sr. in the Washington Post mentioned that the director's actual dad was a little sheepish about how pretentious and mean-spirited the dad character was. But we thought he was wounded and sweet, if exploitative and, indeed, undeniably pretentious.

And the film works well if you take the Walt (Chicken) and Bernard accusation against Mom seriously. She IS disillusioned by Bernard's waning literary success. He's just not as appealing and impressive as when they met. The scene where she articulates this is great, honest in the way the movie is so incredibly honest and vulnerable and revealing and OUCH.

So, then these are the romantic stakes of the film: How sexy is literary success? What happens when creativity is a commodity whose value can be exchanged for sex, love, care, loyalty?

Given these questions, the tastefully materialistic mi$e-en-$cene becomes incredibly meaningful. The Saabs, the neighborhoods, the houses, the furniture, the rugs, the books, the books, the books. If I saw this again I'd keep a tally of titles - a cute paperback of Elements of Style prominantly displayed, Bernard Malamud, and after that I lost track.

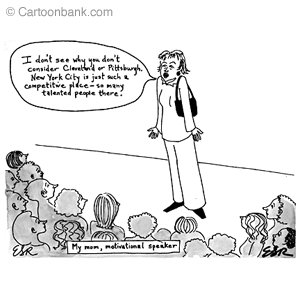

And the competitive talent show becomes a brilliant, pivotal moment - Walt wins $100 for playing a Pink Floyd song he pretends he wrote and starts to think he's hot shit. We liked the idea that he thinks he's hot shit because his trick exposed how wretched the idea of a competitive talent show is, but this motivation isn't explicit in the film. But that's cool.

My favorite scenes were the one-on-one scenes - Mom and Walt, Mom and Dad on the stoop, and Walt and his psychologist. Note: Psychologist is not white. Everyone else who speaks in the film is. I also thought Sophie was a great actor. Actually, all the kids were amazing actors and very beautiful with lovely voices.

Why all the plot and psychology analysis, ZP? Aren't you a film studies grad student? Well, it's that kind of movie. Pretty, and the group scenes often have a sense of visual and emotional chaos, but it's not the most visually experimental of films. To be honest, it includes a montage of views out a subway window. Enough said. But this is sort of intercut with the boys in the car making the same trip and, it seems, this is how they mostly travel. Actually, the in the car scenes are tense and claustrophobic and scary.

Based on (I assume) the visual style and the psychological themes, the Washington Post thing described the film as "realism" but I don't know. A morally loaded family story, set to plaintive music? Consider the following, from that same essay by Thomas Elsaesser I quoted last week. Melodrama, not realism, is

“icongraphically fixed by the claustrophobic atmosphere of the bourgeois home and/or the small-town setting, its emotional pattern is that of panic and latent hysteria, reinforced stylistically by a complex handling of space in interiors to the point where the world seems totally predetermined and pervaded by ‘meaning’ and interpretable signs” (183)

Granted, New York isn't a small town, but you can imagine that this little gentrifiying corner of Brooklyn is treated as such. And also,

"Melodramas often used middle-class American society, its iconography and the family experience [...] as their manifest 'material' , but 'displace' it into quite different patterns, juxtaposing stereotyped situations in strange configurations, provoking clashes and ruptures which not only open up new associations but also redistribute the emotional energies which suspense and tensions have accumulated, in disturbingly different directions. American movies, for example, often manipulate very shrewdly situations of extreme embarassment (a blocking of emotional energy) and acts or gestures of violence (direct or indirect release) in order to create patterns of aesthetic signficance [...] (from Movies and Methods,181)

Bingo! Genre! Melodrama!

To strengthen this claim, I'd ask you to compare The Squid and the Whale to Meet Me in St. Louis, a musical and a melodrama about waning patriarchial power and where the family is going to live. I would especially compare little Pickle (Frank, top image, on the bottom) to the unsocialized child, played by Margaret O'Brien (left, duh) in Meet Me in St. Louis. Dad even mentions Truffaut's The Wild Child in a conversation with him, in the great tradition of unsocialized children (thanks Aaron for all your unsocialized child suggestions over the years). These are good scenes too, at the ping-pong table, a very competitive space, as I well know.

To strengthen this claim, I'd ask you to compare The Squid and the Whale to Meet Me in St. Louis, a musical and a melodrama about waning patriarchial power and where the family is going to live. I would especially compare little Pickle (Frank, top image, on the bottom) to the unsocialized child, played by Margaret O'Brien (left, duh) in Meet Me in St. Louis. Dad even mentions Truffaut's The Wild Child in a conversation with him, in the great tradition of unsocialized children (thanks Aaron for all your unsocialized child suggestions over the years). These are good scenes too, at the ping-pong table, a very competitive space, as I well know. A breif summary of the two kids: Sings a Racist Song, Threatens the Neighbors, Fakes a Streetcar Accident, Demolishes Snow Family. Masturbates at School, Drinks Excessively, Plays Tennis, Uses Profanity. You match them up.

The photos I've chosen lead me to my final point, a question of misbehavior and gender. Given the emotional attention paid to Walt, Frank and Bernard, this might count as a masculine melodrama (note the boxing gloves and thanks to Rebecca, for introducing me to this idea oh so long ago) and, to some extent, it falls into the trap of making Mom and her sexuality the mysterious force that drives the narrative. But, on the other hand, it does pay a lot of attention to kids and their agenderousness, in a nice, sweet way.

Oh yeah, and Denby liked the movie too. It figures. Review was in Oct 24 Issue. He adds that it is funny and it is.

Categories: film, newyorker

Sensory Experiences: visual, aural, spatial